Should I respond or not? I mentally shifted gears several times, veering between amusement and annoyance. Several weeks before, I had read an opinion piece in The Nation, one of the most prominent newspapers in Thailand, which claimed that the international school that the writer’s children attended performed poorly in teaching STEM subjects. In his view this resulted directly from the school’s reluctance to hire non-Western teachers (who were deemed as superior in those areas), and he claimed “it is the same in all international schools in Thailand.” A few days later, a second submission took the claim a step further, decrying the hiring of teachers with “mere elementary education degrees” and declaring that those with science and engineering backgrounds (the “smartest graduates”) would be better equipped to teach English.

Neither of the opinion pieces presented evidence to support their claims, nor did they consider the highly varied nature of international schools in Thailand. Being an educator who has worked in the field for over a decade, and someone who simply doesn’t like to let misconceptions rest, I penned a response, What (some) international schools are doing right, systematically addressing each of the points that had been raised. Not all international schools are the same. Many do hire non-Western teachers, including my own. Educational research has consistently shown that trained teachers using pedagogical approaches that incorporate conceptual understandings and inquiry have the greatest impact in the long term. Universities and employers indicate that they want graduates with greater soft skills, not solely technical expertise.

To me, this type of discourse is natural. A claim is made. Evidence is assessed. An argument is presented. But then the Google alert arrived in my inbox. A reply to the brief article I had written was posted, beginning with the equivalent of a schoolyard taunt:

“I think Jared Kuruzovich urgently needs the services of an Asian teacher who could teach him to write concisely. His grandiloquent essay was a big yawn.”

Never mind the irony of using the term grandiloquent (and the racist connotations that the writer claimed to be standing against). At no point was evidence presented to back the original claims. At no point was it mentioned that those claims in both his article and the subsequent one did not align with research, surveys of universities and employers, and standardized test data. At no point were the counterarguments addressed.

It all boiled down to essentially calling me a pretentious doody head.

In 2008 noted programmer and entrepreneur Paul Graham wrote an essay on his website, How to Disagree, that detailed the deterioration of discourse on the internet. The points he raised over a decade ago are more salient than ever, easily evidenced by the comments section on Yahoo! or any other major online news outlet. We relish disagreement, but we have increasingly lost the ability to present our opinions in a cogent, reasoned manner.

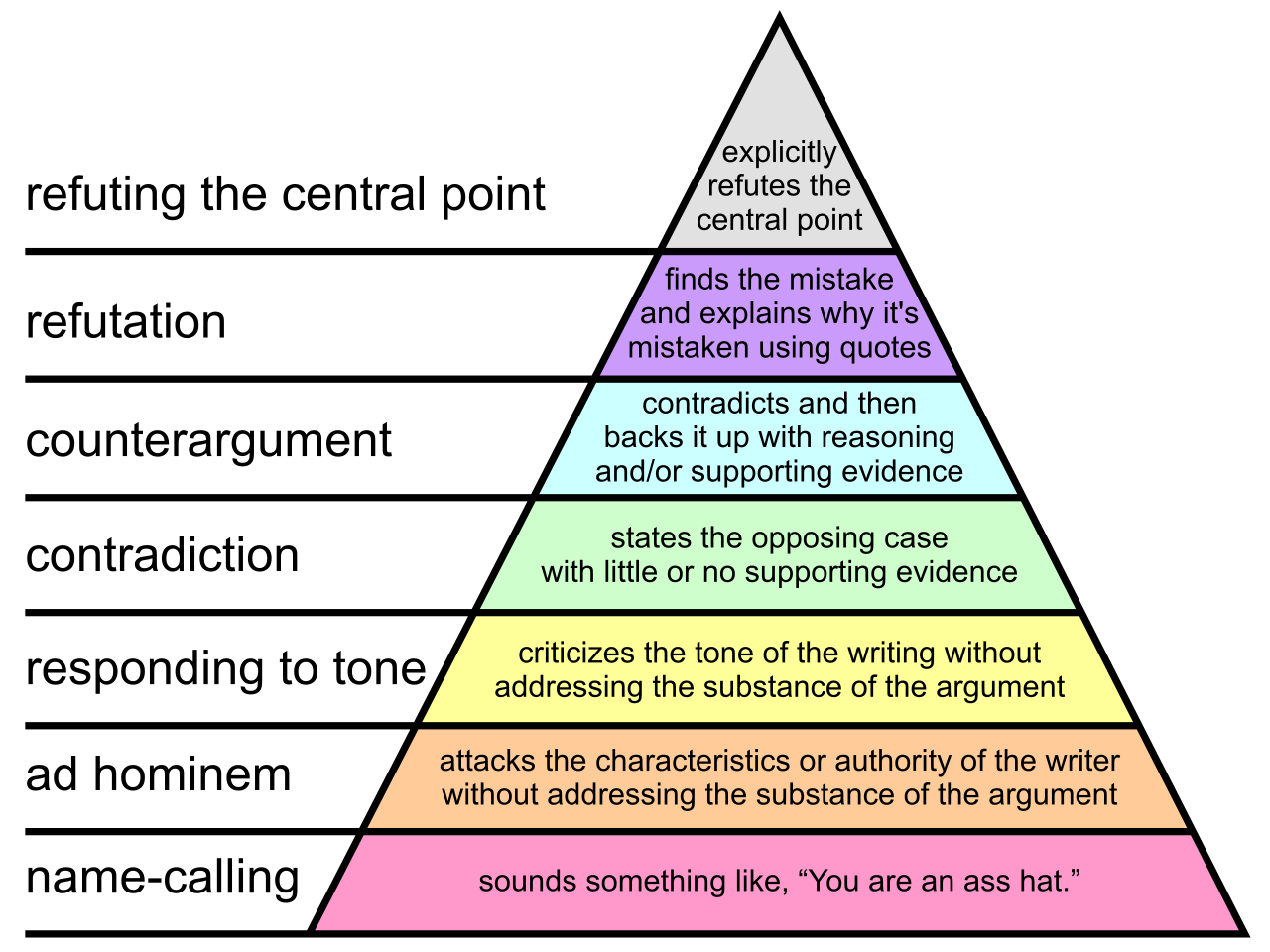

Graham broke this down into the Hierarchy of Disagreement, with name calling and ad hominem attacks occupying the lowest tiers and direct refutation representing the most effective approach. Despite the obvious importance of methodically analyzing and responding to evidence when debating or simply arguing, consider how rare this often is even for politicians and everyday citizens. We resort to labels, whether liberal, conservative, extremist, intellectual, redneck or many far less eloquent terms.

These kinds of insults are nothing new and have been present in debate from the time of the Greek philosophers. But the age of mass media has impacted us in ways we could not have fully foreseen. Conclusive figures are difficult to gather, but we do know that the prevalence of reading has been in steady decline, while the amount of time spent on smartphones and other technology continues to rise. Though the internet has made information more accessible than ever, a gradual trend toward media snippets and sound bites has created a culture of instant gratification, and in the process the patience required to read even an essay or listen to a reasoned debate has been lost.

I dread the future of society if people believe a 1,137 word article is too long. I cringe when the use of rhetoric is equated with pretentiousness. I sigh in exasperation when I hear pundits hurling insults of libtard, radical and elitist. What does it say about our collective intelligence and ability to reason if we cannot consider the views of others and the evidence they offer, regardless of whether we agree or disagree with it? We instead celebrate mediocrity and cheer for name calling. It’s simply easier to ignore, to insult and to dehumanize. And in the process we slowly lose the our ability to reason and, more importantly, to impact others.

One of the clearest examples of this shift away from intellectual debate and rhetoric is seen in the vast differences between American presidents. George W. Bush infamously carried the contest of which candidate voters would prefer to have a beer with in 2004 and, despite being an intelligent person, continued to make headlines for putting his foot in his mouth. When Barack Obama became president in 2008, a common refrain was that he was too intellectual, and the election of Donald Trump in some respects felt like a reactionary call to arms as many voters rejected a style of leadership they labeled as arrogant.

What felt like a sharp contrast between Bush and Obama became a gaping chasm when comparing Obama and Trump. While Obama embraced the nuances and complexities of issues, and openly addressed them with deliberate oratory techniques, Trump’s patterns of speech throw all the rules out the window. His stream-of-consciousness approach is punctuated by pauses as crowds cheer and exhibit virtually no logical structure or a desire to incorporate evidence for his wild statements. Excerpts from their speeches say far more than I can:

The genius of our founders is that they designed a system of government that can be changed. And we should take heart, because we’ve changed this country before. In the face of tyranny, a band of patriots brought an Empire to its knees. In the face of secession, we unified a nation and set the captives free. In the face of Depression, we put people back to work and lifted millions out of poverty. We welcomed immigrants to our shores, we opened railroads to the west, we landed a man on the moon, and we heard a King’s call to let justice roll down like water, and righteousness like a mighty stream.

Each and every time, a new generation has risen up and done what’s needed to be done. Today we are called once more – and it is time for our generation to answer that call. For that is our unyielding faith – that in the face of impossible odds, people who love their country can change it. That’s what Abraham Lincoln understood. He had his doubts. He had his defeats. He had his setbacks. But through his will and his words, he moved a nation and helped free a people. It is because of the millions who rallied to his cause that we are no longer divided, North and South, slave and free. It is because men and women of every race, from every walk of life, continued to march for freedom long after Lincoln was laid to rest, that today we have the chance to face the challenges of this millennium together, as one people – as Americans.

Look, having nuclear—my uncle was a great professor and scientist and engineer, Dr. John Trump at MIT; good genes, very good genes, OK, very smart, the Wharton School of Finance, very good, very smart—you know, if you’re a conservative Republican, if I were a liberal, if, like, OK, if I ran as a liberal Democrat, they would say I’m one of the smartest people anywhere in the world—it’s true!—but when you’re a conservative Republican they try—oh, do they do a number—that’s why I always start off: Went to Wharton, was a good student, went there, went there, did this, built a fortune—you know I have to give my like credentials all the time, because we’re a little disadvantaged—but you look at the nuclear deal, the thing that really bothers me—it would have been so easy, and it’s not as important as these lives are (nuclear is powerful; my uncle explained that to me many, many years ago, the power and that was 35 years ago; he would explain the power of what’s going to happen and he was right—who would have thought?), but when you look at what’s going on with the four prisoners—now it used to be three, now it’s four—but when it was three and even now, I would have said it’s all in the messenger; fellas, and it is fellas because, you know, they don’t, they haven’t figured that the women are smarter right now than the men, so, you know, it’s gonna take them about another 150 years—but the Persians are great negotiators, the Iranians are great negotiators, so, and they, they just killed, they just killed us.

Ideological differences aside, there is a clear difference between these two men in style and an even clearer divide in their ability to present a reasoned argument. Trump is notorious for attacking and denigrating others, building his case by belittling opponents rather than relying on clear, reasonable arguments and evidence to support his views. His approach is replicated thousands, if not millions, of times every day across the internet. Yet as Graham pointed out in his essay, “if you have something real to say, being mean just gets in the way.”

The bottom line is that constructing a logical, reasoned argument does not make a person pompous. Intelligence should not be portrayed as a character flaw, and using effective rhetoric should be celebrated in the same way that we celebrate good writing in literature and film. When we take the time to listen to the views of others, consider their arguments and present a logical response, we’re giving them the same respect that we want to be treated with. Unfortunately, it appears that incivility is not going away, as many now celebrate the online culture of insults, particularly within American politics.

I for one think that if making a polite, reasoned case for my views makes me a grandiloquent doody head, I’ll take it.

.